|

|

M

Maccabaeans A priestly Jewish family which ruled Palestine in the second and first centuries BCE (164 - 67 BCE) and wrested Judaea from the rule of the Seleucids and their Greek practices. The Jewish holiday Hanukkah commemorates the Maccabees' recapture of Jerusalem and re-consecration of the Temple in December 164 BCE A name often used for the Hasmonaeans. The term derives from the surname of Judas Maccabeus, the early leader of the revolt against Antiochus Epiphanes. Macedon was the name of a kingdom centred in the northernmost part of ancient Greece. The homeland of the ancient Macedonians, it was bordered by the kingdom of Epirus to the west and the region of Thrace to the east. For a brief period it became the most powerful state in the world after Alexander the Great conquered most of the world known to the Greeks, inaugurating the Hellenistic period of world history. Machaerus Another Jewish fortress of ancient Palestine lying southeast of Qumran across the Dead Sea at a distance of only twenty kilometers. Qumran lies almost halfway, as the crow flies, between Jerusalem and Machaerus. This fortress was built or at least strengthened by the Hasmonaean Alexander Jannaeus after he subjugated Moab to the east of the Dead Sea sometime before 90 BCE. It was designated as a bulwark to fend off attacks by the Aramaic-speaking Nabataeans who occupied Petra and areas to the south. Destroyed by Gabinius, the governor of Syria, circa 60 BCE, it was rebuilt by Herod the Great, and his son Antipas murdered John the Baptist there.

Nothing is known of the configuration of the burial cave, as entrance to it is forbidden. It has been suggested that it may originally have been a rock-cut shaft tomb, of the type common around 2000 B.C. Likewise, there is no knowledge of the mode of burial practiced by the patriarchs, except for the obvious fact that the cave was reused over several generations for successive burials. The massive Herodian walls that enclosed a large, rectangular open air temenos have remained intact. The open rectangle, however, was built up in later periods with a succession of churches and mosques, which produced the rather confusing structure now standing on the site. The cenotaphs and tombstones now standing in the mosque and pointed out as the burial sites of the patriarchs, are of the Mameluk period or later.

Madaba map A sixth century CE map of Palestine, forming the mosaic floor of a Byzantine church located in the ancient town of Madaba (Medeba) modern al-'Asimah, in what is now west-central Jordan. It preserves many important details of the geography of Roman and Byzantine Palestine.

It was the scene of many events in the life of the Buddha.

Magahi See Magahi language

The Magadhi language is a language spoken by 17,449,446 people in India. The ancestor of Magadhi, from which its name derives, Magadhi Prakrit, is believed to be the language spoken by the Buddha, and the language of the ancient kingdom of Magadha. Magadhi is closely related to Bhojpuri and Maithili and these languages are sometimes referred to as a single language, Bihari. These languages, together with several other related languages, are known as the Bihari languages, which form a sub-group of the Eastern Zone group of Indo-Aryan languages. Magadhi has approximately 13 million speakers. It was once mistakenly thought to be dialects of Hindi, but has been more recently shown to be descendant of and very similar to Eastern Group of Indic languages, along with Bengali, Assamese, and Oriya. It has a very rich and old tradition of folk songs and stories. It is spoken in 8 districts in Bihar, 3 in Jharkhand and has some speakers in Malda, West Bengal. Despite of the large number of speakers of Magadhi, it has not been constitutionally recognized in India. Even in Bihar, Hindi is the language used for educational and official matters. Magahi was legally absorbed under the subordinate label of Hindi in the 1961 Census. Such state and national politics are creating conditions for language endangerments.

Magic is a conceptual system that asserts human ability to control or predict the natural world (Nature [including events, objects, people, and physical phenomena]) through mystical, paranormal or supernatural means. The term can also refer to the practices employed by a person asserting this ability, and to beliefs that explain various events and phenomena in such terms. In many cultures the concept of magic is under pressure from, and in competition with, scientific and religious conceptual systems. This is particularly the case in the Christian West and the Muslim Middle East where the practice of magic is generally regarded as blasphemous or forbidden by orthodox leadership. An action or effort undertaken because of a personal need to effect change, especially as associated with Wicca or Wiccan beliefs. The spelling with the terminal "k" was repopularized in the first half of the 20th century by Aleister Crowley when he introduced it as a core component of Thelema. For Crowley, the alternate spelling was used to differentiate it from other practices, such as stage magic. Magick is not capable of producing "miracles" or violating the physical laws of the universe (e.g., it cannot cause a solar eclipse), although "it is theoretically possible to cause in any object any change of which that object is capable by nature". Crowley preferred the spelling magick, defining it as "the science and art of causing change to occur in conformity with the will." By this, he included "mundane" acts of will as well as ritual magic. In Magick in Theory and Practice, Chapter XIV, Crowley says: What is a Magical Operation? It may be defined as any event in nature which is brought to pass by Will. We must not exclude potato-growing or banking from our definition. Let us take a very simple example of a Magical Act: that of a man blowing his nose. Crowley saw magick as the essential method for a person to reach true understanding of the self and to act according to one's True Will, which he saw as the reconciliation "between freewill and destiny." Crowley describes this process: One must find out for oneself, and make sure beyond doubt, who one is, what one is, why one is . . . Being thus conscious of the proper course to pursue, the next thing is to understand the conditions necessary to following it out. After that, one must eliminate from oneself every element alien or hostile to success, and develop those parts of oneself which are specially needed to control the aforesaid conditions. Since the time of Crowley's writing about magick, many different spiritual and occult traditions have adopted the spelling with the terminal -k, but have redefined what it means to some degree. For many modern occultists, it refers strictly to paranormal magic, which involves influencing events and physical phenomena by supernatural, mystical, or paranormal means.

The Hebrew shophetim, or judges, were magistrates having authority in the land (Deut. 1:16-17). In Judg. 18:7, the word “magistrate” (A.V.) is rendered in the Revised Version “possessing authority,” i.e., having power to do them harm by invasion. In the time of Ezra (9:2) and Nehemiah (2:16; 4:14; 13:11) the Jewish magistrates were called seganim, properly meaning “nobles.” In the New Testament, the Greek word archon, rendered “magistrate” (Luke 12:58; Titus 3:1), means one first in power, and hence a prince, as in Matt. 20:25, 1 Cor. 2:6, 8. This term is used of the Messiah, “Prince of the kings of the earth” (Rev. 1:5). In Acts 16:20, 22, 35-36, 38, the Greek term strategos, rendered “magistrate,” properly signifies the leader of an army, a general, one having military authority. The strategoi were the duumviri, the two praetors appointed to preside over the administration of justice in the colonies of the Romans. They were attended by the sergeants (properly lictors or “rod bearers”). Mahalath Mahalath is the name of a tune or a musical term.

Although the Mahayana movement traces its origin to Gautama Buddha, scholars believe that it originated in India in the 1st century CE, or the 1st century BCE. Scholars think that Mahayana only became a mainstream movement in India in the fifth century CE, since that is when Mahayanic inscriptions started to appear in epigraphic records in India. Before the 11th century CE (while Mahayana was still present in India), the Mahayana Sutras were still in the process of being revised. Thus, several different versions may have survived of the same sutra. These different versions are invaluable to scholars attempting to reconstruct the history of Mahayana. In the course of its history, Mahayana spread throughout East Asia. The main countries in which it is practiced today are China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam and worldwide amongst Tibetan Buddhist practitioners as a result of the Himalayan diaspora following the Chinese invasion of Tibet. The main schools of Mahayana Buddhism today are Pure Land, Zen, Nichiren Buddhism, Shingon, Tibetan Buddhism and Tendai. The latter three schools have both Mahayana and Vajrayana practice traditions. See also Sila

A Malakh is a messenger angel who appears throughout the Hebrew Bible, Rabbinic literature, and traditional Jewish liturgy. In modern Hebrew, mal'akh is the general word for "angel." The Hebrew Bible reports that Malakhim appeared to each of the patriarchs (Bible), to Moses, Joshua, and numerous other figures. They appear to Hagar in Genesis 16:9, to Lot in Genesis 19:1, and to Abraham in Genesis 22:11, they ascend and descend Jacob's Ladder in Genesis 28:12 and appear to Jacob again in Genesis 31:11-13. God promises to send one to Moses in Exodus 33:2, and sends one to stand in the way of Balaam in Numbers 23:31. Isaiah speaks of Malakh Panov, "the angel of His presence" (Isaiah 3:9). The Book of Psalms says "For malakhav (His angels) He will charge for you, to protect you in all your ways" (Psalms 91:11) Maleficium is a Latin term meaning "wrongdoing" or "mischief" and is used to describe malevolent, dangerous, or harmful magic, "evildoing" or "Malevolent Sorcery" In general, the term applies to any magical act intended to cause harm or death to people or property. The term appears in several historically important texts and circumstances. Notably the Formicarius, and the malleus maleficarum. The Knights Templar were also accused of maleficium. The Trial of the Knights Templar set a social standard for the popular belief in maleficium and witchcraft which contributed to the great European witch hunt. Malkuth or Shekhinah is the tenth of the sephirot in the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. It sits at the bottom of the Tree, below Yesod. This sephirah has as a symbol the Bride which relates to the sphere of Tipheret, symbolized by the Bridegroom. Unlike the other nine sephirot, it is an attribute of God which does not emanate from God directly. Rather it emanates from God's creation -- when that creation reflects and evinces God's glory from within itsel. Malkuth means Kingdom. It is associated with the realm of matter/earth and relates to the physical world, the planets and the solar system. It is important not to think of this sephirah as merely "unspiritual," for even though it is the emanation furthest from the divine source, it is still on the Tree of Life. As the receiving sphere of all the other sephirot above it, Malkuth gives tangible form to the other emanations. It is like the negative node of an electrical circuit. The divine energy comes down and finds its expression in this plane, and our purpose as human beings is to bring that energy back around the circuit again and up the Tree. Some occultists have also likened Malkuth to a cosmic filter, which lies above the world of the Qliphoth, or the Tree of Death, the world of chaos which is constructed from the imbalance of the original sephirot in the Tree of Life. For this reason it is associated with the feet and anus of the human body, the feet connecting the body to Earth, and the anus being the body's "filter" through which waste is excreted, just as Malkuth exretes unbalanced energy into the Qliphoth. The archangel of this sphere is Sandalphon, and the Ishim (souls of fire) is the Angelic order. The name of God is Adonai Melekh or Adon ha-Arets. There is also a connection to the tenth card of each suit in Tarot. Symbols associated with this sphere are a Bride (a young woman on a throne with a veil over her face) and a double cubed altar. Where Binah is known as the Superior Mother, this sphere is referred to as the Inferior Mother. It is also referred to as the bride of Macroprosopos, where Macroprosops is Kether. From a Christian viewpoint this sphere is important since Jesus preached that we should "seek first the Kingdom of God". In some systems, it is equated with Daat, knowledge, the invisible sephirah. In comparing with Eastern systems, Malkuth is a very similar archetypal idea to that of the Muladhara chakra, in Shakta tantra, which is also associated with the Earth, the plane in which karma is expressed. Although Malkuth is seen as the lowest Sefirah on the tree of life, it also contains within it the potential to reach the highest. This is exemplified in the Hermetic maxim 'As above so below'.

"No servant can serve two masters," Jesus told his disciples. "For either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and mammon." These words are from the Sermon on the Mount, as recorded in Matthew 6:24. Of course, Jesus didn't say them in English. He spoke Aramaic, a Semitic language in the Afro-Asiatic language family. But thanks to what Jesus said and did, one of the words in this modern English translation is the same as in the original. A speaker of ancient Aramaic would recognize mammon. The word was delivered unchanged from Aramaic to the Greek of the New Testament, from Greek to Latin, and eventually to English. Apparently there was nothing else in Greek, Latin, or English that would exactly translate mammon, which means "wealth as an object of desire and false worship." Its earliest English appearance is as wealth personified in William Langland's allegorical Piers Plowman of 1362. The character named Dobet (that is, "Do Better") does what Jesus urged: "with Mammon's money he has made himself friends, has turned to religion, has translated the Bible, and preaches to the people St. Paul's words." Aramaic is both younger and older than its close relative Hebrew. In Jesus' time it was a modern language, compared to Hebrew, but unlike Hebrew it has not been revived after it died out more than a thousand years ago with the spread of Arabic-speaking Islam. Although no one speaks Aramaic nowadays, one descendant, Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, is spoken by 30,000 people in Syria, another 30,000 in Iraq, and fully 80,000 in the United States, and another descendant, Chaldean Neo-Aramaic, is spoken by more than 100,000 in Iraq and 70,000 in the United States. A few other biblical and religious words in English also come from ancient Aramaic, including abbot (880) from abba meaning "father" and Pharisee (897), as well as the Jewish kaddish and tefillin (both 1613).

Dualistic religion founded by Mani in Persia in the 3rd century AD. Inspired by a vision of an angel, Mani viewed himself as the last in a line of prophets that included Adam, Buddha, Zoroaster, and Jesus. His writings, now mostly lost, formed the Manichaean scriptures. Manichaeism held that the world was a fusion of spirit and matter, the original principles of good and evil, and that the fallen soul was trapped in the evil, material world and could reach the transcendent world only by way of the spirit. Zealous missionaries spread its doctrine through the Roman empire and the East. Vigorously attacked by both the Christian church and the Roman state, it disappeared almost entirely from Western Europe by the end of the 5th century but survived in Asia until the 14th century. See also dualism Manicheism See Manicheanism

The union of a husband and a wife for the purpose of cohabitation, procreation, and to enjoy each other's company. God's plan for marriage is between one man and one woman (Mark 10:6-9; 1 Corinthians 7). Although there are many cases of a man marrying more than one woman in the Old Testament, being married to one wife is a requirement to serve in certain church leadership positions (1 Timothy 3:2,12; Titus 1:5-6).

Person who voluntarily suffers death rather than deny his or her religion. Readiness for martyrdom was a collective ideal in ancient Judaism, notably in the era of the Maccabees, and its importance has continued into modern times. Roman Catholicism sees the suffering of martyrs as a test of their faith. Many saints of the early church underwent martyrdom during the persecutions of the Roman emperors. Martyrs need not perform miracles to be canonized. In Islam, martyrs are thought to comprise two groups of the faithful: those killed in jihad and those killed unjustly. In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is regarded as a martyr because he voluntarily postpones enlightenment to alleviate the suffering of others.

Masada Important Jewish fortress of ancient Palestine situated on a butte west of the Dead Sea; last stronghold of the 960 Jewish Zealots, including their wives and children, who volunteered to be killed or committed suicide, rather than surrender to the besieging Roman army at the end of the final battle of the revolt that marks the end of the Second Temple Period. Located thirty-three miles South of Qumran. Maschil Maschil is a musical and literary term for "contemplation" or "meditative psalm."

The Ben Asher family of masoretes was largely responsible for the preservation and production of the Masoretic Text, although an alternate Masoretic text of the Ben Naphtali masoretes which differs slightly from the Ben Asher text existed. The halakhic authority Maimonides endorsed the Ben Asher as superior, although Saadya Gaon had preferred the Ben Naphtali system. The Masoretes devised the vowel notation system for Hebrew that is still widely used as well as the trope symbols used for cantillation.

The Masoretic Text is the Hebrew text of the Jewish Bible (Tanakh). It defines not just the Books of The Jewish canon, but also the precise letter-text of the biblical books in Judaism, as well as their vocalization and accentuation for both public reading and private study. The MT is also widely used as the basis for translations of the Old Testament in Protestant Bibles, and in recent decades also for Catholic Bibles. The MT was primarily copied, edited and distributed by a group of Jews known as the Masoretes between the seventh and tenth centuries AD. Though the consonants differ little from the text generally accepted in the early second century (and also differ little from some Qumran texts that are even older), it has numerous differences of both greater and lesser significance when compared to (extant 4th century) manuscripts of the Septuagint, a Greek translation (made in the 3rd to 2nd centuries BC) of the Hebrew Scriptures that was in popular use in Egypt and Palestine and that is often quoted in the Christian New Testament. The Hebrew word mesorah refers to the transmission of a tradition. In a very broad sense it can refer to the entire chain of Jewish tradition (see Oral law), but in reference to the masoretic text the word mesorah has a very specific meaning: the diacritic markings of the text of the Hebrew Bible and concise marginal notes in manuscripts (and later printings) of the Hebrew Bible which note textual details, usually about the precise spelling of words.

The oldest extant fragments of the

Masoretic Text date from approximately the ninth century AD, and the

Aleppo Codex (the oldest copy of the Masoretic Text, but missing the

Torah) dates from the tenth century. Public celebration of the life, death and resurrection of Christ involving the central act of the Eucharist The Mass is the Eucharistic celebration in the Latin liturgical rites of the Roman Catholic Church. The term is used also of similar celebrations in Old Catholic Churches, in the Anglo-Catholic tradition of Anglicanism, and in some largely High Church Lutheran regions, including the Scandinavian and Baltic countries. For the celebration of the Eucharist in Eastern Churches, including those in full communion with the Holy See, other terms, such as the Divine Liturgy, the Holy Qurbana, and the Badarak, are normally used. Most Western denominations not in full communion with the Roman Catholic Church, such as Calvinist Christianity, also usually prefer terms other than Mass.

The term "Mass" is

derived from the late-Latin word missa (dismissal), a word

used in the concluding formula of Mass in Latin: "Ite, missa est" ("Go;

it is the dismissal"). There are no known societies that are unambiguously matriarchal, although there are a number of attested matrilinear, matrilocal and avunculocal societies, especially among indigenous peoples of Asia, such as those of the Minangkabau or Mosuo. Strongly matrilocal societies sometimes are referred to as matrifocal, and there is some debate concerning the terminological delineation between matrifocality and matriarchy. Note that even in patriarcjical systems of male-preference primogeniture there may occasionally be queen regnants, as in the case of Elizabeth I of England or Victoria of the United Kingdom.

In 19th century scholarship, the

hypothesis of matriarchy representing an early stage of human

development — now mostly lost in prehistory, with the exception

of some "primitive" societies — enjoyed popularity.

The hypothesis survived into the 20th century and was notably

advanced in the context of feminism and especially second wave

feminism, but it is mostly discredited today.

2. A musical setting of certain parts of the Mass, especially the Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei.

Matthew's Bible was the combined work of three individuals, working from numerous sources in at least five different languages. The Pentateuch, the Books of Joshua, Judges, Ruth, First and Second Samuel, First and Second Kings, and First and Second Chronicles-as well as the entire New Testament first published in 1526 and later revised-were the work of William Tyndale. Tyndale worked directly from the Hebrew and Greek, occasionally consulting the Vulgate and Erasmus's Latin version, and referencing Luther's Bible for the prefaces and marginal notes. The use of the pseudonym "Thomas Matthew" resulted from the need to conceal from Henry VIII the participation of Tyndale in the translation. The remaining books of the Old Testament and the Apocrypha were the work of Myles Coverdale. Coverdale translated primarily from German and Latin sources (see Coverdale Bible). The Prayer of Manasses was the work of John Rogers. Rogers translated from a French Bible printed two years earlier (in 1535). Rogers compiled the completed work and added the preface, some marginal notes, a calendar and almanac. Of the three translators, two were burned at the stake. Tyndale was burned on 6 October 1536 in Vilvoorde, Belgium at the instigation of agents of Henry VIII and the Anglican Church. John Rogers was "tested by fire" on 4 February 1554/55 at Smithfield, England; the first to meet this fate under Mary I of England. Myles Coverdale was employed by Cromwell to work on the Great Bible of 1539, the first officially authorized English translation of the Bible. Historians often tend to treat Coverdale and Tyndale like competitors in a race to complete the monumental and arduous task of translating the biblical text. One is often credited to the exclusion of the other. In reality they knew each other and occasionally worked together. Foxe states that they were in Hamburg translating the Pentateuch together as early at 1529. Time and extensive scholastic scrutiny have judged Tyndale the most gifted of the three translators. Dr Westcott in his History of the English Bible states that "The history of our English Bible begins with the work of Tyndale and not with that of Wycliffe." The quality of his translations has also stood the test of time, coming relatively intact even into modern versions of the Bible. Matsah See Matza

Matza is the substitute for bread during the Jewish holiday of Passover, when eating chametz—bread and leavened products—is forbidden. Eating matza on the night of the seder is considered a positive mitzvah, i.e., a commandment. In the context of the Passover seder meal, certain restrictions additional to the chametz prohibitions are to be met for the matza to be considered "mitzva matza", that is, matza that meets the requirements of the positive commandment to eat matza at the seder. Matzah See Matza Matzoh See Matza

The holiest city of Islam, it was the birthplace of the Prophet Muhammad. It was his home until AD 622, when he was forced to flee to Medina (see also Hijrah); he returned and captured the city in 630. It came under the control of the Egyptian Mamluk dynasty in 1269 and of the Ottoman Empire in 1517. King Ibn Sa'ud occupied it in 1925, and it became part of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. It is a religious centre to which Muslims must attempt a pilgrimage (see hajj) once during a lifetime; only Muslims may enter Mecca. Services related to pilgrimages are the main economic activity. It is the site of the Haram Mosque, which contains the Ka'bah. mediaeval See Middle Ages medieval See Middle Ages

The term Mediterranean derives from the Latin word mediterraneus, meaning "in the middle of earth" (medius, "middle" + terra, "land, earth"). This is either due to the sea being surrounded by land (especially compared to the Atlantic Ocean) or that it was at the center of the known world. The Mediterranean Sea has been known by a number of alternative names throughout human history. For example the Romans commonly called it Mare Nostrum (Latin, "Our Sea"). Occasionally it was known as Mare Internum by (Sallust, Jug. 17). Other examples of alternate names include Mesogeios, meaning "inland, interior" in Greek. Biblically, it has been called the "Hinder Sea", due to its location on the west coast of the Holy Land, and therefore behind a person facing the east, as referenced in the Old Testament, and sometimes translated as "Western Sea", (Deut. 11:24; Joel 2:20), and also the "Sea of the Philistines" (Exod. 23:31), due to the peoples occupying a large portion of its shores near the Israelites. However, primarily it was known as the "Great Sea" (Num. 34:6,7; Josh. 1:4, 9:1, 15:47; Ezek. 47:10,15,20), or simply "The Sea" (1 Kings 5:9; comp. 1 Macc. 14:34, 15:11). In Modern Hebrew, it has been called Hayam Hatikhon, "the middle sea", a literal adaptation of the German equivalent Mittelmeer. In Turkish, it is known as Akdeniz, "the white sea". In modern Arabic, it is known as "the Middle Sea." And, lastly, in Islamic and older Arabic literature, it was referenced as bahr al-room or "the Roman Sea." Mare Internum (Mare Nostrum). Lat. names for Mediterranean (Biblical name 'Great Sea'). Great Sea, The (Mediterranean Sea) Biblical name: Num. 34:6, 7; Josh. 1:4; 9:1; 15:12; 23:4; Ezek. 47:10; 48:28. Assyrian-Babylonian name 'The Upper Sea', 'The Western Sea'; Latin 'Mare Internum', 'Mare Nostrum.' All the rains that shower the hills and water the valleys of Palestine come from the Mediterranean. And the wonderful dews which, with the regularity of clockwork, settle during the rainless season in the cool of the evening upon the Palestinian hills. The harvest, whether of grain or fruit, is nourished by these heavy dews.

Mediumship is believed by its

adherents to be a form of communication with spirits. It is a

practice in religious beliefs such as Spiritualism,

Spiritism, Espiritismo,

Candomblé, Louisiana

Voodoo, and Umbanda.

While the Western movements of Spiritualism and Spiritism account for

most Western news-media exposure, most African and African-diasporic

traditions include mediumship as a central focus of religious practice.

a lake in Northern Palestine through which the Jordan flows It was the scene of the third and last great victory gained by Joshua over the Canaanites (Josh. 11:5-7). It is not again mentioned in Scripture. Its modern name is Bakrat el-Huleh. "The Ard el-Huleh, the center of which the lake occupies, is a nearly level plain of 16 miles in length from north to south, and its breadth from east to west is from 7 to 8 miles. On the west it is walled in by the steep and lofty range of the hills of Kedesh-Naphtali; on the east it is bounded by the lower and more gradually ascending slopes of Bashan; on the north it is shut in by a line of hills hummocky and irregular in shape and of no great height, and stretching across from the mountains of Naphtali to the roots of Mount Hermon, which towers up at the northeastern angle of the plain to a height of 10,000 feet. At its southern extremity the plain is similarly traversed by elevated and broken ground, through which, by deep and narrow clefts, the Jordan, after passing through Lake Huleh, makes its rapid descent to the Sea of Galilee." The lake is triangular in form, about 4 1/2 miles in length by 3 1/2 at its greatest breadth. Its surface is 7 feet above that of the Mediterranean. It is surrounded by a morass, which is thickly covered with canes and papyrus reeds, which are impenetrable. Macgregor with his canoe, the Rob Roy, was the first that ever, in modern times, sailed on its waters.

The name of one place and two biblical men&ldots; A plain in that part of the boundaries of Arabia inhabited by the descendants of Joktan (Gen. 10:30).

Messiah literally means "anointed (one)". Figuratively, anointing (in antiquity done with holy anointing oil) is done to signify being chosen for a task; so, messiah means "the chosen (one)", particularly someone divinely chosen. In Jewish messianic tradition and eschatology, messiah refers to a future King of Israel from the Davidic line, who will rule the people of united tribes of Israel and herald the Messianic Age of global peace. In Standard Hebrew, The Messiah is often referred to as literally meaning "the Anointed King." Christians believe that prophecies in the Hebrew Bible refer to a spiritual savior, and believe Jesus to be that Messiah (Christ). In the (Greek) Septuagint version of the Old Testament, khristos was used to translate the Hebrew, meaning "anointed." In Islam, Isa (Jesus) is also called the Messiah (Masih), but like in Judaism he is not considered to be the Son of God. The Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek translates all thirty-nine instances of the word messiah as (Khristós). The New Testament records the Greek transliteration Messias, twice, in John 1:41 and 4:25.

The most prominent instance of this occurs in Mark 8:27-30: Jesus went on with his Disciples to the villages of Caesarea Philippi; and on the way he asked his Disciples, 'Who do people say I am?' (28) And they answered him, 'John the Baptist; and others, Elijah; and still others, one of the prophets.' (29) He asked them, 'But who do you say that I am?' Peter answered him, 'You are the Messiah.' (30) And he sternly ordered them not to tell anyone about him. As noted pointedly by W. R. Telford, Jesus commands his followers to silence after healings and exorcisms. When Jesus heals a leper, he commands the man not to spread the news of his miraculous healing: (43) After sternly warning him he sent him away at once, (44) saying to him, 'See that you say nothing to anyone; but go, show yourself to the priest, and offer for your cleansing what Moses commanded, as a testimony to them.' (45) But he went out and began to proclaim it freely, and to spread the word, so that Jesus could no longer go into a town openly, but stayed out in the country; and people came to him from every quarter. (Mark 1.43-45) Luke 8:10: He said, "The knowledge of the secrets of the kingdom of God has been given to you, but to others I speak in parables, so that, " 'though seeing, they may not see; though hearing, they may not understand.'" (NIV) Matthew 13:10-12: The Disciples came to him and asked, "Why do you speak to the people in parables?" He replied, "The knowledge of the secrets of the kingdom of Heaven has been given to you, but not to them. Whoever has will be given more, and he will have an abundance. Whoever does not have, even what he has will be taken from him." (NIV) Methodist See Methodism

Early Methodists were drawn from all levels of society, including aristocracy. But the Methodist preachers took the message to labourers and criminals who tended to be left outside of organised religion at that time. Wesley himself thought it wrong to preach outside a Church building until persuaded otherwise by Whitefield. Doctrinally, the branches of Methodism following the Wesleys are Arminian, while those following Harris and Whitefield are Calvinistic. Wesley did not let this difference of interpretation change his friendship with Whitefield, and Wesley's sermon on Whitefield's death is full of praise and affection. Methodism has a very wide variety of forms of worship, ranging from high church to low church in liturgical usage. The Wesleys themselves greatly valued the Anglican liturgy and tradition, and based Methodist worship in The Book of Offices on the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. Methodist Beliefs Traditionally, most Methodists have identified with the libertarian-Arminian view of free will, through God's prevenient grace, as opposed to the determinism of absolute predestination. This distinguishes it, historically, from Calvinist traditions found in Reformed churches. However, in strongly Reformed areas such as Wales, Calvinistic Methodists remain, also called the Presbyterian Church of Wales. The Calvinist Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion was also strongly associated with the Methodist revival. In recent theological debates, clergy members have cut across denominational lines so that theologically left-leaning Methodist and Reformed churches have more in common with each other than with more conservative members of their own denominations. John Wesley is studied for his interpretation of Church practice and doctrine (Explanatory Notes by Methodist ministerial students and trainee local preachers). One popular expression of Methodist doctrine is in the hymns of Charles Wesley. Since enthusiastic congregational singing was a part of the early Evangelical movement, Wesleyan theology took root and spread through this channel. Methodism affirms the traditional Christian belief in the triune Godhead: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, as well as the orthodox understanding of the consubstantial humanity and divinity of Jesus. Most Methodists also affirm the Apostles Creed and the Nicene Creed. In devotional terms, these confessions are said to embrace the biblical witness to God's activity in creation, encompass God's gracious self-involvement in the dramas of history, and anticipate the consummation of God's reign. Sacramental theology within Methodism tends to follow the historical interpretations and liturgies of Anglicanism. This stems from the origin of much Methodist theology and practice within the teachings of John and Charles Wesley, both of whom were priests of the Church of England. As affirmed by the Articles of Religion, Methodists recognize two Sacraments as being ordained of Christ: Baptism and Holy Communion. Methodism also affirms that there are many other Means of Grace which often function in a sacramental manner, but most Methodists do not recognize them as being Dominical sacraments. Methodists, stemming from John Wesley's own practices of theological reflection, make use of Tradition as a source of authority. Though not on the same level as Holy Scripture, tradition may serve as a lens through which Scripture is interpreted (see also Prima scriptura and the Wesleyan Quadrilateral). Theological discourse for Methodists almost always makes use of Scripture read inside the great Tradition of Christendom It is a historical position of the church that any disciplined theological work calls for the careful use of reason. By reason, it is said, one reads and interprets Scripture. By reason one determines whether one's Christian witness is clear. By reason one asks questions of faith and seeks to understand God's action and will. The church insists that personal salvation always implies Christian mission and service to the world. Scriptural holiness entails more than personal piety; love of God is always linked with love of neighbors and a passion for justice and renewal in the life of the world. A distinctive liturgical feature of Methodism is the use of Covenant services. Although practice varies between different national churches, most Methodist churches annually follow the call of John Wesley for a renewal of their covenant with God. It is not unusual in Methodism for each congregation to normally hold an annual Covenant Service on the first convenient Sunday of the year, and Wesley's Covenant Prayer is still used, with minor modification, in the order of service. In it, Wesley avers man's total reliance upon God, as the following excerpt demonstrates: . . . Christ has many services to be done. Some are easy, others are difficult. Some bring honour, others bring reproach. Some are suitable to our natural inclinations and temporal interests, others are contrary to both... Yet the power to do all these things is given to us in Christ, who strengthens us. . . . I am no longer my own but yours. Put me to what you will, rank me with whom you will; put me to doing, put me to suffering; let me be employed for you or laid aside for you, exalted for you or brought low for you; let me be full, let me be empty, let me have all things, let me have nothing; I freely and wholeheartedly yield all things to your pleasure and disposal . . . Whereas most Methodist worship is modeled after the Anglican Communion's Book of Common Prayer, a unique feature of the liturgy of the American Methodist Church is its observance of the season of Kingdomtide, which encompasses the last thirteen weeks before Advent, thus dividing the long season after Pentecost into two discrete segments. During Kingdomtide, Methodist liturgy emphasizes charitable work and alleviating the suffering of the poor. Some Methodist churches utilize a more contemporary and less defined liturgy, either in conjunction with traditional Methodist liturgy or in exclusion of it.

a town of Benjamin (Ezra 2:27), east of Bethel and south of Migron, on the road to Jerusalem (Isa. 10:28) It lay on the line of march of an invading army from the north, on the north side of the steep and precipitous Wady es-Suweinit ("valley of the little thorn-tree" or "the acacia"), and now bears the name of Mukhmas. This wady is called "the passage of Michmash" (1 Sam. 13:23). Immediately facing Mukhmas, on the opposite side of the ravine, is the modern representative of Geba, and behind this again are Ramah and Gibeah. This was the scene of a great battle fought between the army of Saul and the Philistines, who were utterly routed and pursued for some 16 miles towards Philistia as far as the valley of Aijalon. "The freedom of Benjamin secured at Michmash led through long years of conflict to the freedom of all its kindred tribes." The power of Benjamin and its king now steadily increased. A new Spirit and a new hope were now at work in Israel. michtam A michtam is a poem.

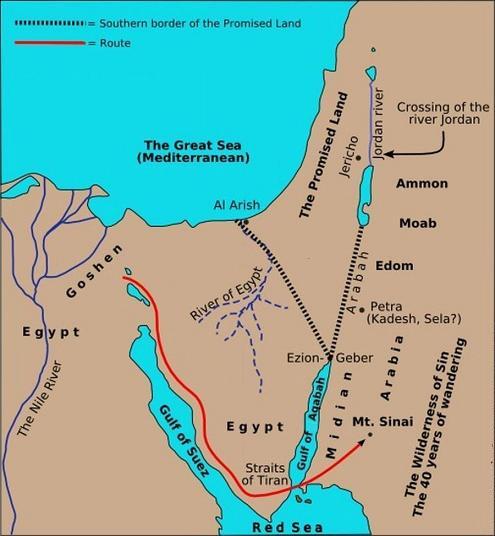

In Bible history, Midian was where Moses spent the 40 years between the time that he fled Egypt after killing an Egyptian who had been beating an Israelite, and his return for leading the Israelites. During those years, he married Zipporah, the daughter of Jethro, the priest of Midian. Exodus 3:1 implies that God's appearance in the burning bush at Mount Horeb occurred in Midian. As the Bible asserts, in later years the Midianites were often oppressive and hostile to the Israelites, at least partly as God's punishment for their idolatry. By the time of the Judges, the Midianites, led by two princes Oreb (Hebrew: Orev) and Zeeb (Hebrew: Z'ev) were raiding Israel with the use of swift camels, until they were decisively defeated by Gideon. Today, the former territory of Midian is located in what is now a small area of western Saudi Arabia, southern Jordan, southern Israel and the Sinai. Midian spaned from Mount Horhab located at Elat at the head of the Gulf of Aqaba North to Moab sharing a border with Edom which runs up the Arabah through Petra to the Dead Sea. Midian contains the land to the southeast of that border as far south as Jokuban and as far east as the Crystal Plateau containing much of northwestern Saudi Arabia. In the Book of Genesis, Midian was the son of Abraham and his last wife Keturah whom he married after the death of his old wife Sarah. Midian's five sons, Ephah, Epher, Enoch, Abida, and Eldaah, were the progenitors of the Midianites. The term "Midian", which may be derived from the Semitic root word for judgment, denotes also the nation of the Midianites; the plural form occurring only in Genesis 37:28,36 and Numbers 25:17, 31:2. In The Book of Genesis Midian is described as having been to the east of Canaan; Abraham sends the sons of his concubines, including Midian, eastward. Its geographic location is anchored in Exodus by the statement that Moses led the flocks of Jethro, the priest of Midian, to Mount Horeb Exodus 3:1) and by the fact that Moses met up with Jethro in Midian while the sons of Israel were at Mount Horab after crossing the Red Sea and Voyaging up the Gulf of Aqaba to Elat. 9. Dophkah Nu. 33:12-13 "Dophkah" from the Semitic root for Adonis, a Phoenician emporia at Elat Egyptiam suburb of modern Elat 10. Alush Nu. 33:13-14 the summit of Horeb where the water flowed from the rock Mt Horab at modern Elat and where Moses met up with Jethro 11. Rephidim Ex. 17:1, 19:2; Nu. 33:14-15 near Mt. Horab at Elat Place of rhe First Contact with the Amalek and Rephidim of the Negev, Edom, and Canaan 12. Sinai Wilderness Ex. 19:1-2; Nu. 10:12, 33:15-16 The campsites near Elat A dozen sites with Egyptian artifacts have been found at Timnah near Elat 13. Kibroth-Hattaavah Taberah Nu. 11:1, Nu. 11:35, 33:16-17 lit. Graves of Longing or Graves of Lust The burials of those who fought the Amalek at Horab The remainder of the stations of the Exodus circumnavigate Edom heading north up the border of Edom with the Sinai to the brook of Egypt, then East to Moab and the Dead Sea, then south through Petra to Elat and back to Canaan. The Midianites dwelt in the Arabah bordering the Negev occupied by Edom and Northwestern Saudia Arabia up as far as Moab which is modern Jordan. Midian is likewise described as in the vicinity of Moab: the Midianites were beaten by the Edomite king Hadad ben Bedad "in the field of Moab", and in the account of Balaam it is said that the elders of both Moab and Midian called upon him to curse Israel. The period in European history between antiquity and the Renaissance, often dated from A.D. 476 to 1453. Period in European history traditionally dated from the fall of the Roman Empire to the dawn of the Renaissance. In the 5th century the Western Roman Empire endured declines in population, economic vitality, and the size and prominence of cities. It also was greatly affected by a dramatic migration of peoples that began in the 3rd century. In the 5th century these peoples, often called barbarians, carved new kingdoms out of the decrepit Western Empire. Over the next several centuries these kingdoms oversaw the gradual amalgamation of barbarian, Christian, and Roman cultural and political traditions. The longest-lasting of these kingdoms, that of the Franks, laid the foundation for later European states. It also produced Charlemagne, the greatest ruler of the Middle Ages, whose reign was a model for centuries to come. The collapse of Charlemagne's empire and a fresh wave of invasions led to a restructuring of medieval society. The 11th – 13th centuries mark the high point of medieval civilization. The church underwent reform that strengthened the place of the pope in church and society but led to clashes between the pope and emperor. Population growth, the flourishing of towns and farms, the emergence of merchant classes, and the development of governmental bureaucracies were part of cultural and economic revival during this period. Meanwhile, thousands of knights followed the call of the church to join the Crusades. Medieval civilization reached its apex in the 13th century with the emergence of Gothic architecture, the appearance of new religious orders, and the expansion of learning and the university. The church dominated intellectual life, producing the Scholasticism of St. Thomas Aquinas. The decline of the Middle Ages resulted from the breakdown of medieval national governments, the great papal schism, the critique of medieval theology and philosophy, and economic and population collapse brought on by famine and disease. Middle Kingdom of Egypt See The Middle Kingdom

See also halakha

a place between Aiath and Michmash (Isa. 10:28) The town of the same name mentioned in 1 Sam. 14:2 was to the south of this. mikvah See Mikveh

Its main uses nowadays are:

Also See Mikva'ot

Tractate Mikva'ot is a section of the Mishna discussing the laws pertaining to the building and maintenance of a Mikvah, a Jewish ritual bath. Like most of Seder Tohorot, Mikva'ot is present only in its mishnaic form and has no accompanying gemara in either the Babylonian or Jerusalem Talmud.

More generally and without the definite article, any identified span of 1?000 years can be called a millennium. Note that ‘the millennium’ is also used to mean the end-point of such a time period. mina A mina is a Greek coin worth 100 Greek drachmas (or 100 Roman denarii), or about 100 day's wages for an agricultural laborer.

Minhag is an accepted tradition or group of traditions in Judaism. A related concept, Nusach, refers to the traditional order and form of the prayers. Arabic: minha-j also means custom or tradition, though not necessarily religious tradition. The Hebrew root N-H-G means primarily "to drive" or, by extension, "to conduct (oneself)". The actual word minhag appears twice in the Hebrew Bible, both times in the verse: And the watchman told, saying: 'He came even unto them, and cometh not back; and the driving (minhag) is like the driving (minhag) of Jehu the son of Nimshi; for he driveth furiously.' (II Kings 9:20) Homiletically, one could argue that the use of the word minhag in Jewish law reflects its Biblical Hebrew origins as "the (manner of) driving (a chariot)". Whereas Halakha (law), from the word for walking-path, means the path or road set for the journey, minhag (custom), from the word for driving, means the manner people have developed themselves to travel down that path more quickly. The present use of minhag for custom may have been influenced by the Arabic minhaj, though in current Islamic usage this term is used for the intellectual methodology of a scholar or school of thought (cf. Hebrew derech) rather than for the customs of a local or ethnic community. Orthodox Jews consider Halakha, Jewish law as derived from the Talmud, binding upon all Jews. However, in addition to these halakhot, there have always been local customs and prohibitions. Some customs were eventually adopted universally (e.g. wearing a head covering) or almost universally (e.g. monogamy). Others are observed by some major segments of Jewry but not by others (e.g., not eating rice on Passover).

In religion, term used to designate the clergy of Protestant churches, particularly those who repudiate the claims of apostolic succession. The ceremony by which the candidate receives the office of a minister is called ordination. Protestant ordination, unlike holy orders in the Roman Catholic Church, is not a sacrament. The Reformation doctrine of the “priesthood of all believers” underlies the inclination of many Protestant bodies to reduce the distinction between ministry and laity. In certain Protestant groups, e.g., the Plymouth Brethren, the ordination of ministers is dispensed with altogether. The Society of Friends (Quakers) ordains but makes little practical distinction between ministers and laity. Lutheranism and Presbyterianism invest the office with great dignity. Methodism (in the United States but not in Great Britain) has an episcopal form of church organization but one quite unlike the episcopacy of the Church of England. Fundamental to most Protestant groups is the belief that the soul can go to God without the need of priestly mediation. Hence the function of the ministry is interpreted strictly as one of assistance to the religious life through preaching, the administration of sacraments, and counseling.

In the Hebrew Bible the writings of the minor prophets are counted as a single book, in Christian Bibles as twelve individual books. The "Twelve" are listed below in order of their appearance in Hebrew and most Protestant and Catholic Christian bibles:

Hosea The Septuagint of the Eastern churches has the order: Hosea, Amos, Micah, Joel, Obadiah, Jonah, the rest as above. It also puts the "Minor Prophets" before, instead of after, the "Major prophets". Recent biblical scholarship has focused on reading the "Book of the Twelve" as a unity. The term "minor" refers to the length of the books, not their importance. See Major Prophets for the longer books of prophecies in the Bible and the Tanakh. The twelve minor prophets are collectively commemorated in the Calendar of saints of the Armenian Apostolic Church on July 31. In the Roman Catholic Church, the twelve minor prophets are read in the Breviary during the fourth and fifth weeks of November, which are the last two weeks of the liturgical year. Minor Prophets See Minor Prophet

The minor tractates are essays from the Tannaitic period or later dealing with topics about which no formal tractate exists in the Mishnah. They may thus be contrasted to the Tosefta, whose tractates parallel those of the Mishnah. The first eight or so contain much original material; the last seven or so are collections of material scattered throughout the Talmud. The Minor Tractates are normally printed at the end of Seder Nezikin in the Talmud. They include: 1. Avot of Rabbi Natan. The Schechter edition contains two different versions (version A has 41 chapters and version B has 48). 2. Soferim (Scribes). This tractate appears in two different versions in the Jerusalem and Babylonian Talmuds. 3. Evel Rabbati. This tractate is about laws and customs pertaining to death and mourning, and is sometimes euphemistically called Semakhot ("joys"). 4. Kallah (on engagement, marriage and co-habitation). 5. Kallah Rabbati (an elaboration of the above). 6. Derekh Eretz Rabbah. "Derekh Eretz" literally means "the way of the world," which in this context refers to deportment, manners and behavior. 7. Derekh Eretz Zutta. Addressed to scholars, this is a collection of maxims urging self examination and modesty. 8. Pereq ha-Shalom (on the ways of peace between people; a final chapter to the above often listed separately). 9. Sefer Torah (regulations for writing Torah scrolls). 10. Mezuzah (scroll affixed to the doorpost). 11. Tefillin (phylacteries). 12. Tzitzit (fringes). 13. Avadim (servants). 14. Gerim (conversion to Judaism). 15. Kutim (Samaritans). There is also a lost tractate called "Eretz Yisrael" (The Land of Israel, about laws of that land.)

See also:

The Mishneh Torah, subtitled Sefer Yad ha-Chazaka, is a code of Jewish religious law (Halakha) by one of the important Jewish authority Maimonides (Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, also known by the Hebrew abbreviation RaMBaM, usually written "Rambam" in English). The Mishneh Torah was compiled between 1170 and 1180, while he was living in Egypt, and is regarded as Maimonides' magnum opus. The work consists of 14 books, subdivided into sections, chapters and paragraphs. It is the only Medieval work that details all of Jewish observance, including those laws which are only applicable when the Holy Temple is in place. The word "Mishnah" also means "Secondary", thus named for being both the one written authority (codex) secondary (only) to the Tanakh as a basis for the passing of judgement, a source and a tool for creating laws, and the first of many books to complement the Bible in a certain aspect. The Mishnah does so by presenting actual cases being brought to judgement, usually presents the debate on the matter as it was, and relays the judgement which was given by a wise and notable rabbi, based on the rules, Mitzvot, and spirit of the "Torah" which guided his sentencing, thus bringing to every-day reality the rules and the practice or adherence of the "Mitzvot" as presented in the Bible. In other words, the Mishnah teaches strictly by example and is case-based, though associative in structure, it aimed to cover all aspects of human living, set an example in its own for future judgements and, most importantly, demonstrate pragmatic exercise of the biblical laws, which was much needed at the time when the Second Temple was destroyed. The Mishnah reflects debates between 70-200 AD by the group of rabbinic sages known as the Tannaim and redacted about 200 AD by Judah haNasi when, according to the Talmud, the persecution of the Jews and the passage of time raised the possibility that the details of the oral traditions would be forgotten. The oral traditions that are the subject of the Mishnah go back to earlier, Pharisaic times. The Mishnah does not claim to be the development of new laws, but merely the collection of existing traditions. The Mishnah is considered to be the first important work of Rabbinic Judaism and is a major source of later rabbinic religious thought. Rabbinic commentaries on the Mishnah over the next three centuries were redacted as the Gemara. The Mishnah consists of six orders (sedarim, singular seder), each containing 7-12 tractates (masechtot, singular masechet; lit. "web"), 63 in total. Each masechet is divided into chapters (peraqim, singular pereq) and then paragraphs or verses (mishnayot, singular Mishnah). The Mishnah is also called Shas (an acronym for Shisha Sedarim - the "six orders"). The Mishnah orders its content by subject matter, instead of by biblical context, and discusses individual subjects more thoroughly than the Midrash. It includes a much broader selection of halakhic subjects than the Midrash.

In each order (with the exception of Zeraim), tractates are arranged from biggest (in number of chapters) to smallest. The word Mishnah can also indicate a single paragraph or verse of the work itself, ie. the smallest unit of structure in the Mishnah.

Mistletoe is known popularly as the plant sprig that people kiss beneathduring the Christmas season. That custom dates back to pagan times when, according to legend, the plant was thought to inspire passion and increase fertility. Norse mythology recounts how the god Balder was killed using a mistletoe arrow by his rival god Hoder while fighting for the female Nanna. Druid rituals use mistletoe to poison their human sacrificial victim. The Christian custom of “kissing under the mistletoe” is a later synthesis of the sexual license of Saturnalia with the Druidic sacrificial cult.

Mitzvah is a word used in Judaism to refer to the 613 commandments given in the Torah and the seven rabbinic commandments instituted later for a total of 620. The term can also refer to the fulfilment of a mitzvah. The term mitzvah has also come to express any act of human kindness, such as the burial of the body of an unknown person. According to the teachings of Judaism, all moral laws are, or are derived from, divine commandments. The opinions of the Talmudic rabbis are divided between those who seek the purpose of the mitzvot and those who do not question them. The latter argue that if the reason for each mitzvah could be determined, people might try to achieve what they see as the purpose of the mitzvah, without actually performing the mitzvah itself. The Hebrew word mitzvot means "commandments" (mitzvah is its singular form). Although the word is sometimes used more broadly to refer to rabbinic (Talmudic) law or general good deeds - as in, "It would be a mitzvah to visit your mother" - in its strictest sense it refers to the divine commandments given by God in the Torah. Jewish rituals and religious observances are grounded in Jewish law (halakhah, lit. "the path one walks.") An elaborate framework of divine mitzvot, or commandments, combined with rabbinic laws and traditions, this law is central to Judaism. Halakhah governs not just religious life, but daily life, from how to dress to what to eat to how to help the poor. Observance of halakhah shows gratitude to God, provides a sense of Jewish identity and brings the sacred into everyday life.

Mizrahi Jews are those Jews of Middle Eastern origin; that is to say, their ancestors never left the Middle East. Though many Mizrahim now follow the liturgical traditions of the Sephardim, and although in modern Israel they may be colloquially referred to as Sephardic Jews, the Mizrahim are not Sephardic since they have never lived in Sepharad (Spain and Portugal) nor are they descended of those who were expelled from the Iberian peninsula during the Spanish Inquisition. Many Mizrahim may consider it culturally insensitive or ignorant not to distinguish between the two communities, even if some Mizrahi may themselves have come to accept the generalized label, despite its erroneous application. Prior to the emergence of the term "Mizrahi", which dates from their transportation and incorporation into the newly created state of Israel - Arab Jews was a commonly used designation, though not by Mizrahi Jews. The term, however, is rarely used today, and Mizrahi Jews generally self-identify by their country of origin (e.g. "Iraqi Jew") or often simply as Sephardi. Compare with the synonymity of Ashkenazi and European Jew, or Sephardi and Iberian Jew. Unlike the terms Ashkenazi and Sephardi, Mizrahi is simply a convenient way to refer collectively to a wide range of Jewish communities, most of which are as unrelated to each other as they are to either the Sephardi or Ashkenazi communities. See also: Jewish ethnic divisions.

Ugaritic inscriptions refer to Egypt as Msrm, in the Amarna tablets it is called Misri, and Assyrian and Babylonian records called Egypt Musur and Musri. The Arabic word for Egypt is Misr (pronounced Masr in colloquial Arabic), and Egypt's official name is Gumhuriyah Misr al-'Arabiyah (the Arab Republic of Egypt). According to The Book of Genesis (Ge-10), Mizraim was the younger brother of Cush and elder brother of Phut and Canaan, whose families together made up the Hamite branch of Noah's descendants. Mizraim's sons were Ludim, Anamim, Lehabim, Naphtuhim, Pathrusim, Casluhim (out of whom came the Philistines), and Caphtorim. According to Eusebius' Chronicon, Manetho had suggested that the great age of antiquity in which the later Egyptians boasted had actually preceded the Flood, and that they were really descended from Mizraim, who settled there anew. A similar story is related by mediaeval Islamic historians such as Sibt ibn al-Jawzi, the Egyptian Ibn Abd-el-Hakem, and the Persians al-Tabari and Muhammad Khwandamir, stating that the pyramids, etc. had been built by the wicked races before the Deluge, but that Noah's descendant Mizraim (Masar or Mesr) was entrusted with reoccupying the region afterward. The Islamic accounts also make Masar the son of a Bansar or Beisar and grandson of Ham, rather than a direct son of Ham, and add that he lived to the age of 700. Some scholars think it likely that Mizraim is a dual form of the word Misr meaning "land", and was translated literally into Ancient Egyptian as Ta-Wy (the Two Lands) by early pharaohs at Thebes, who later founded the Middle Kingdom. But according to George Syncellus, the Book of Sothis, supposedly by Manetho, had identified Mizraim with the legendary first pharaoh Menes, said to have unified the Old Kingdom and built Memphis. Misraim also seems to correspond to Misor, said in Phoenician mythology to have been father of Taautus who was given Egypt, and later scholars noticed that this also recalls Menes, whose son or successor was said to be Athothis. In Judaism, Mitzrayim has been connected with the word meitzar, meaning "sea strait", possibly alluding to narrow gulfs from both sides of Sinai peninsula. It also can mean "boundaries, limits, restrictions" or "narrow place".

Moabite may refer to:

modalism See Sabellianism modalistic monarchianism See Sabellianism modal monarchism See Sabellianism Modern Orthodox See Modern Orthodox Judaism Modern Orthodoxy See Modern Orthodox Judaism

Modern Orthodox Judaism is a movement within Orthodox Judaism that attempts to synthesize traditional observance and values with the secular, modern world. Modern Orthodoxy draws on several teachings and philosophies, and thus assumes various forms. In the United States, and generally in the Western world, "Centrist Orthodoxy" — underpinned by the philosophy of Torah Umadda ("Torah and Knowledge/Science") — is prevalent. In Israel, Modern Orthodoxy is dominated by Religious Zionism; however, although not identical, these movements share many of the same values and many of the same adherents.

Liberation is experienced in this very life as a dissolution of the sense of self as an egoistic personality by which the underlying, eternal, pure spirit is uncovered. This desireless state concludes the yogic path through which conditioned mentality-materiality or nama-roopa (lit. name-form) has been dissolved uncovering one's eternal identity prior to the mind/spirit's identification with material form. Liberation is achieved by (and accompanied with) the complete stilling of all passions — a state of being known as Nirvana. Advaita Vedantist thought differs slightly from the Buddhist reading of liberation.

Local community or residence of a religious order, particularly an order of monks. Christian monasteries originally developed in Egypt, where the monks first lived as isolated hermits and then began to coalesce in communal groups. Monasteries were later found throughout the Christian world and often included a central space for church, chapels, fountain, and dining hall. In the Middle Ages they served as centres of worship and learning and often played an important role for various European rulers. The vihara was an early type of Buddhist monastery, consisting of an open court surrounded by open cells accessible through an entrance porch. Originally built in India to shelter monks during the rainy season, viharas took on a sacred character when small stupas and images of the Buddha were installed in the central court. In western India, viharas were often excavated into rock cliffs. See also abbey.

A man who is a member of a brotherhood living in a monastery and devoted to a discipline prescribed by his order: a Carthusian monk; a Buddhist monk. In modern parlance also referred to as a monastic, is a person who practices religious asceticism, the conditioning of mind and body in favor of the spirit, and does so living either alone or with any number of like-minded people, whilst always maintaining some degree of physical separation from those not sharing the same purpose. The concept is ancient and can be seen in many religions and in philosophy. In the Greek language the term can apply to men or women; but in modern English it is in use only for men, while nun is used for female monastics. Although the term monachos (“monk”) is of Christian origin, in the English language it tends to be used analogously or loosely also for ascetics from other religious or philosophical backgrounds. The term monk is generic and in some religious or philosophical traditions it therefore may be considered interchangeable with other terms such as ascetic. However, being generic, it is not interchangeable with terms that denote particular kinds of monk, such as cenobite, hermit, anchorite, hesychast, solitary.

The doctrine that in the person of Jesus

Christ there was but one, divine, nature, rather than two natures,

divine and human. A point of dispute between the Coptic and

Abyssinian churches, which accept the doctrine, and Roman

Catholicism, which denies it in favour of the opposing, dyophysite

doctrine of two natures.

Moriah is the name given to a mountain range by The Book of Genesis, in which context it is given as the location of the near sacrifice of Isaac. Traditionally Moriah has been interpreted as the name of the specific mountain at which this occurred, rather than just the name of the range. The exact location referred to is currently a matter of some debate.

Mormon Church See The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The term derives from the word Mormon, which was originally used as a pejorative term to describe those who believed in the Book of Mormon, a sacred text that adherents believe to be "another testament of Jesus Christ" and testifies of the Bible as part of the religion's canon. There are many subsects of Mormonism, all of which claim to be the true interpretation of Joseph Smith's original teachings. It is common for the different denominations of Mormonism to object to use of the term by other groups. The LDS Church, the largest subsect of Mormonism, states that the term is only "acceptable in describing the combination of doctrine, culture and lifestyle unique to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints." Historically the term has been used very broadly and can mean members of the LDS Church, smaller offshoot faiths, or members of Fundamentalist Mormon faiths, with little agreement on a definitive use. Because of the diversity of beliefs among various Mormon sects, the basic tenets of Mormonism can only be described in the broadest sense. The foundation of Mormonism is that Joseph Smith, Jr. was visited by God the Heavenly Father and His Son, Jesus Christ. These divine beings instructed him that he was to join no organized religion and that he was to prepare himself for a greater work that would follow. Joseph Smith later brought forth (The Book of Mormon) that was written by ancient Christian Prophets who lived in the American Continent, and he also restored what he called the true religion as founded by Jesus Christ himself, with all rites, rituals, and doctrines as they were in primitive Christianity.

Saturday night, immediately following the end of the Sabbath.

Coordinates: 39°42?N 44°17?E / 39.7°N 44.283°E / 39.7; 44.283 The Mountains of Ararat is the place named in The Book of Genesis where Noah's ark came to rest after the Great Flood (Genesis 8:4). Abrahamic tradition associates the mountains of Ararat with Mount Ararat in Turkey located 750 miles (1200 kilometers) northeast of Jerusalem. Mount Ararat was, for many centuries, part of the Armenian states, it eventually fell into the hands of the Ottoman Empire and later the Persian Empire (Iran). After the Russo-Persian War, 1826-1828 and the Treaty of Turkmenchay it was incorporated into the Russian Empire as part of the Armenian Oblast and later the Erivan Governate. After World War I, it came under the administration of the Democratic Republic of Armenia as part of the Ararat province but was ceded to Turkey by the Soviet Union in the Treaty of Kars. Historians have long sought to corroborate the biblical reference to the "mountains of Ararat" with Mount Ararat, or to ascertain the actual location of the mountains mentioned in the account. The Book of Jubilees specifies that the Ark came to rest on one of the peaks of the "Mountains of Ararat" called "Lubar". Some have sought to connect the name "Ararat" with ancient states in the area such as Urartu, and the even older "Aratta" found in Sumerian records. These cultures were centered around Lake Van in ancient Armenia during Biblical times (currently in Turkey). Mount Ararat has the distinction of holding this tradition among its surrounding cultures for centuries, and is also geographically within ancient Urartu, giving it the most legitimate potential claim as the Biblical Ararat. However, the Biblical account could plausibly have been intended to refer to any of the mountain ranges associated with Urartu. An obvious problem associated with identifying the resting place of the Ark is that its elevation must be lower than the ultimate depth of the Flood water, since the Biblical account indicates that the highest point of land was covered to a depth of about twenty feet. An elevation higher than a certain point would require an impossible rate of rainfall to cover it. In the view of some biblical literalists, it is dubious that a peak of over 16,000 feet would even exist at the time of the Flood; hence the facts imply that the mountains of "Ararat" were much lower than today, even if they were the highest in the world, a position not supported by modern geomorphology. Other potential Ararat candidates have been proposed over the millennia at locales as widely distributed as Ethiopia, Ireland, and Iran. The Latin Vulgate says "requievitque arca super montes Armeniae", which means literally "and the ark rested on the mountains of Armenia", which was corrected to " mountains of Ararat" (montes Ararat) in the Nova Vulgata (New Vulgate). In the book, Antiquities of the Jews, Josephus wrote: “The Ark landed on an Armenian mountain peak. Noah, aware now that the earth was safely through the Flood, waited for seven days more. Then he released the animals and went out with his family. He offered a sacrifice to God and then celebrated with a family feast."

Ararat anomaly The Ararat anomaly is an object appearing on photographs of the snowfields near the summit of Mount Ararat and is advanced by some believers in Biblical literalism as the remains of Noah's Ark.

Joshua was buried at Timnath-heres among the mountains of Ephraim, on the north side of the hill of Gaash (Judg. 2:9). This region is also called the "mountains of Israel" (Josh. 11:21) and the "mountains of Samaria" (Jer. 31:5, 6: Amos 3:9).

The Biblical Mount Sinai is an

ambiguously located mountain at which the Hebrew

Bible states that the Ten

Commandments were given to Moses

by God.

In certain biblical passages these events are described as having

transpired at Horeb. Sinai and Horeb are

generally considered to refer to the same place although there is a

small body of opinion that they refer to different locations.

Passages earlier in the narrative text than the Israelite encounter with Sinai indicate that the ground of the mountain was considered holy, but according to the rule of Ein mukdam u'meuchar baTorah -- "[There is] not 'earlier' and 'later' in [the] Torah," that is, the Torah is not authored in a chronological fashion, classical biblical commentators regard this as insignificant. Some modern day scholars, however, who do not recognize the authority of the Oral Law, explain it as having been a sacred place dedicated to one of the Semitic deities, long before the Israelites had ever encountered it. Some modern biblical scholars regard these laws to have originated in different time periods from one another, with the later ones mainly being the result of natural evolution over the centuries of the earlier ones, rather than all originating from a single moment in time. In Classical rabbinical literature, Mount Sinai became synonymous with holiness; indeed, it was said that when the Messiah arrives, God will bring Sinai together with Mount Carmel and Mount Tabor, rebuild the Temple upon the combined mountain, and the peaks would sing a chorus of praise to God. According to early aggadic midrash, Tabor and Carmel had previously been jealous of Sinai having been chosen as the place that the laws were delivered, but were told by God that they had not been chosen because only Sinai had not had idols placed upon it; according to the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer, God had chosen Sinai after discovering that it was the lowest mountain.

There is reason to believe that in Biblical times the name Mount Zion referred to the area of what today is called by Jews the Temple Mount. However, as early as the first century the hill today called Mount Zion had acquired the name for unknown reasons. Important sites on Mount Zion are Dormition Abbey, King David's Tomb and the Room of the Last Supper. The Chamber of the Holocaust (Martef HaShoah), the precursor of Yad Vashem is also located on Mount Zion. Another place of interest is the Catholic cemetery where Oskar Schindler, a Righteous Gentile who saved the lives of 1,200 Jews in the Holocaust, is buried The winding road leading up to Mount Zion is known as Pope's Way (Derekh Ha'apifyor) because it was paved in honor of the historic visit to Jerusalem of Pope Paul VI in 1964. Between 1948 and 1967, this narrow strip of land was a designated no-man's land between Israel and Jordan.

By extension, other religions' feasts are occasionally described by the same term. In addition many countries have secular holidays that are moveable, for instance to make holidays more consecutive; the term "moveable feast" is not used in this case however. Further, by metaphoric extension but with the meaning of a party that was on the move, Ernest Hemingway used the term A Moveable Feast for the title of his memoirs of life in Paris in the 1920s. This usage has become a popular phrase in food contexts, with several catering companies adopting it as their name.

The Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments of God was a breakaway sect from the Roman Catholic Church founded by Credonia Mwerinde and Joseph Kibweteere in Uganda. It formed in the late 1980s after Mwerinde, a brewer of banana beer, and Kibweteere, a politician, claimed that they had visions of the Virgin Mary. The five primary leaders were Joseph Kibweteere, Joseph Kasapurari, John Kamagara, Dominic Kataribabo, and Credonia Mwerinde. In early 2000, followers of the sect perished in a devastating fire, and a series of poisonings and killings, that were either a cult suicide, or an orchestrated mass murder by sect leaders after their predictions of the apocalypse failed to pass. Other than the individuals that died in the fire, medical examiners determined that the majority of dead sect members had been poisoned. Early reports had suggested that they had been strangled based on the presence of twisted banana fibers around their necks. After searching all sites, the police concluded that earlier estimates of nearly a thousand dead had been exaggerated, and that the final death toll had settled at 778. After interviews and an investigation were conducted, the police ruled out a cult suicide, and instead consider it to be a mass murder conducted by Movement leadership. They believe that the failure of the doomsday prophecy led to a revolt in the ranks of the sect, and the leaders set a new date with a plan to eliminate their followers. The discovery of bodies at other sites, the fact the church had been boarded up, the presence of incendiaries, and the possible disappearance of sect leaders all point to this theory. Additionally, witnesses said the Movement leadership had never spoken of mass suicide when preparing members for the end of the world. The Ugandan government responded with condemnation. President Yoweri Museveni has called the event a "mass murder by these priests for monetary gain." Vice president Dr. Speciosa Wandira Kazibwe said, "These were callously, well-orchestrated mass murders perpetrated by a network of diabolic, malevolent criminals masquerading as religious people." Although it was initially assumed that the five leaders died in the fire, police now believe that Joseph Kibweteere and Credonia Mwerinde may still be alive, and have issued an international warrant for their arrest. Mowahhidoon See Druse Mo'wa'he'doon See Druse